The reality of najaf business today

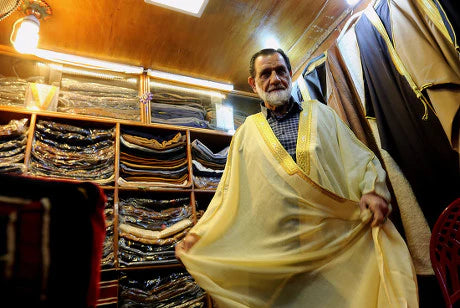

Known across the region for its fine texture, the Najafi abaya is worn by all manner of VIPs from officials to oil-rich sheiks. But the men who produce the hand-made cloth, inheritors of a generations-old trade, are increasingly going out of business.

"Let me tell you something," said Kadhim, laughing bitterly while embroidering one of the full-length cloaks, spread across his lap. "If I could find a government job, I would stop all this.

Kadim, a Najaf Weaver from Iraq

"This work is too hard, and business is not good anymore."

The bazaar where Kadhim has his shop, at the entrance to the shrine to Imam Ali, revered among Shiites, was once dominated by makers of this traditional garb.

Now many stalls sell trinkets, toys and other forms of clothing to pilgrims from mainly Shiite Muslim Iran, as the tradition of hand-made abayas -- those designed and sold in Najaf are only for men -- has seen a dramatic decline in recent years.

The 41-year-old Kadhim, whose family has been in the business so long that he takes the last name Abu Chengal or "father of the crochet hook", does not know if he can hang on much longer.

"My sales of the summer abaya are down to around a fifth of what they were 10 years ago -- I used to sell hundreds but now I sell dozens," he moaned.

What caused a decline in Najaf demand

What caused a decline in Najaf demand

The 2003 U.S. led invasion that ousted Saddam Hussein unleashed a number of changes, from ending the U.N. trade embargo on Iraq and lifting the country's own protectionist policies to pushing up the value of the Iraqi dinar.

The unrest itself caused a sudden drop in demand for the traditional abaya, as fewer customers dared venture to Najaf. And for what orders remained, traditional abaya weavers and tailors found themselves dramatically undercut, prompting many to scramble for secure government jobs.

The new competition came not only from imported textiles, now flooding the market alongside other imported goods, but also from improvements in abaya cloth produced in domestic factories and much cheaper than its hand-made counterpart.

While an embroidered hand-made abaya sells in Najaf's market for between 500,000 and 800,000 Iraqi dinars ($425-$675), factory-made or imported ones can be bought for as little as 75,000 dinars ($65).

"When I quit a few years ago, I was selling each abaya cloth for 120,000 to 150,000 dinars ($100-$125)," lamented Hussein Sayed, 63, a weaver who left the trade in 2005.

The hand-made item is labor intensive, he pointed out, taking one worker three to 10 days to weave cloth for one abaya, even before it is embroidered.

Meanwhile, "you could buy a piece of cloth for an abaya for 20,000 dinars ($17) -- that price was too low, I could not compete," said Sayed. "As soon as international trade began, our jobs were finished.”

Four of his six sons learned the craft but are now taxi drivers.

Why are Najaf businesses are letting go of the tradition

People have moved on –

Razzaq Mohammed, 58, told a similar story -- he dropped weaving to open a general store in 2006 when the craft no longer generated sufficient income.

"It was all we did, my family has done this for more than 100 years -- I opened my eyes at birth, and my family was making abayas this way," he said, standing by three looms kept in a separate room of his home.

"The sheikhs, the VIPs, they still want hand-made Najafi abayas. But the work is not continuous, it is not dependable."

His son Ahmed, 31, still practices the craft, painstakingly unknotting yarn made from sheep wool, warping the loom and weaving abaya panels on the old frame with its series of weights and pulleys affixed to the wall and ceiling. But the amount of work on offer is not enough. "I will leave all this if I find another job that covers the needs of my family," Ahmed said.

A major boost in the Iraqi dinar made the Najafi abaya less attractive to overseas customers -- whereas $1 bought around 3,000 dinars prior to the 2003 invasion, it now gets only 1,180 dinars.

Hassan Issa al-Hakim, who teaches Islamic history at Kufa University in Najaf's twin city, said the industry dates back more than 150 years and the Najafi abaya "represents the identity of the city”. "It was a gift that would be given to political and religious leaders who visited, and it used to be exported across the region," the 69-year-old said. Even now, "there are those who make amazing hand-made abayas but they all depend on requests from clients.”

Back in the "abaya market", as it is still called, Kadhim sat alongside his friend Ahmed al-Ghazali, both life-long abaya tailors. "Look here," Kadhim said waving into the bazaar. "All of this used to be for selling abayas. Not anymore. People have moved on."

The struggles Inaash faces in regards to Najaf

Without doubt the Najaf Abaya and Najaf Shawls, with their intricate designs and lustrous colors are star items at Inaash.

When Inaash started over 50 years ago it wasn’t much of a challenge to put in an order for Najaf fabric and receive high quality quantities in a range of colors. “We used to have the luxury of ordering Najaf fabric whenever we wanted. It was always available, on time, in a colorful range and style, whether soft or hard Najaf. We even returned the Najaf we didn’t want, asked for a different batch, and sometimes went to Syrian Markets to buy there”, says Mrs. Sima Ghandour, a former board member and a current design committee member at Inaash.

But now, things are very different.

Due to the Syrian and Iraqi wars, the Najaf business is really struggling to maintain itself in these sensitive times. “Now we don’t have as many options of Najaf colors as before,” says Samar Kabooli, head of production at Inaash. “In the past we used to control what we received, but now we are restrained by what’s available from the tradesmen, and we work with what we find available.”

The role of Inaash in maintaining the traditional Najaf way

Inaash, however, is totally committed to traditional Najaf, its signature fabric. “We continue to source our wool from traditional hand weavers using artisanal tools. We have been offered synthetic Najaf countless times but we refused, it is not the same fabric. Genuine organic, hand-woven Najaf has more presence and substance to it,” says Samar Kabooli. “Besides, we want to maintain that all our items are 100% hand-made, which won’t be the case if we invest in synthetic manufactured Najaf.”

In seeking to support this ancient, intricate but endangered craft, alongside that of traditional Palestinian embroidery, Inaash commits to produce a range of exceptional, stand out artisanal products that by their very nature are collectors items to be treasured and worn with pride.

By thus sustaining its women embroiderers and the Najaf weavers, Inaash synthesizes two important cultural traditions to produce a range of contemporary designs that are truly outstanding. Which is why for over 50 years it has established and maintained its reputation for excellence.